Early Modern Portuguese army

Moderators: terrys, hammy, Slitherine Core, FOGR Design

-

pippohispano

- Administrative Corporal - SdKfz 251/1

- Posts: 142

- Joined: Thu Sep 23, 2010 4:39 pm

Early Modern Portuguese army

The Early Modern Portuguese society was a society prepared for war, where every able bodied male citizen was supposed to be prepared and equipped for violence. Depending on his income, a man was supposed to supply several pieces of equipment, ranging from simple javelins to arquebuses, from a simple leather head protection to proper helmets and other defensive equipment.

Although the king controlled most aspects of the military apparatus, the nobility still performed many of its old duties, namely the raising of military contingents made either of paid (professional) soldiers or vassals, this including the household (servants, etc.). Personal connections were very important and it was common for a commander to prefer the services of kin or friends as lesser commanders. Experience, however, was not discarded so “old” soldiers were often promoted or sought after for advice.

Throughout the whole XVI century every king, from D. Manuel I to D. Sebastião, tried to implement a system of Ordenanças in which every men were supposed to have certain pieces of equipment (javelins, spears, pikes, swords, crossbows of arquebuses, depending on the person’s income) and every “Concelho” (county) was supposed to raise companies lead by local men. So, in a way, while still adopting a Medieval sense of duty towards the king (the military service, as an obligation, was not paid), these Ordenanças would create a very Modern militia or citizen army, not a standing army but a reserve from which the king could easily raise one.

These Ordenanças, however, had at least two flaws:

Firstly, in the economic sense, this system overburdened the citizens as it was up to them, and not the State, to support the cost of their equipment. Moreover, military service was seldom paid, even to professional soldiers. And the status of these Ordenanças implied that men had to attend periodic musters (in the original Ordenanças, or Regimento dos Capitães-Mores of 1570, these musters would take place every week!), an obligation that was opposed by every man.

Secondly, contrary to established aristocratic prerogatives, the captains of these companies (250 men strong divided in 10 “esquadras”) were chosen from among the notable men in the villages, which meant that the old privileges of the nobility, stipulating that nobles should lead, would be phased out (many nobles lived outside their properties, in Lisbon, for instance). Likewise, people of different “conditions”, that is, of different social strata, opposed to be enrolled into the same company, lesser nobility, or “escudeiros” (squires) preferring to serve in the cavalry instead, even if they couldn’t supply a horse!

Therefore, it is only from 1570 onwards that D. Sebastião, unlike his grandfather D. João III, managed to implement a system of Ordenanças, adapted to the social situation of his time, and managed to raise 4 infantry “Terços” of 2000 men each.

So, for the most part of this period, the army was privately raised, each captain or noble being issued a letter allowing him to raise a company or even an host. The army remained a professional organism where personal links were more important than the obligation towards the State.

The best part of the Portuguese forces was made of “nobres” (nobles), “fidalgos” (lesser nobility) and “soldados” (professional soldiers), most of them expert swordsmen. Their swordsmanship was only equalled by their rashness: although few could stand against Portuguese in solo fights, organised enemies, such as the Dutch, could face and defeat them, in spite of their own losses. This deficiency was due to poor command (often given to inexperienced nobles due only to their social status), carelessness and sometimes an acute lack of training. It is also noteworthy that by mid-XVII cent. many of the soldiers were convicts and vagabonds sent from Lisbon's prisons.

The “casados” (married men) were a social group within the colonists (“moradores”) who were often married with native women. Together with the “mercadores” (merchantmen) they fought in times of need.

While the Portuguese dominion over their colonies was achieved through clear strategic thinking, technological innovations, decisive naval battles and the conquest or foundation of strategic cities such as Goa, Ormuz, Malacca, S. Salvador da Baía, Recife or Rio de Janeiro, the maintenance of the Empire was achieved through political gambling, conversions, matrimonial alliances and, most of all, “mestiçagem” (half-bread), a Portuguese specialty. This, however, didn’t happen in Morocco, deemed as a “land of war”, proper for the gentry and nobility who wished to become famous through deeds of arms.

In 1513, in penance for the killing of his first wife, Duque D. Jaime was sent by the king D. Manuel I to storm the rebellious city of Azamor. He paid from his own pockets a 15.000 strong army (13.000 foot, 2000 horses) and Azamor was taken in 2 days. The frescoes at the Ducal Palace of Vila Viçosa show pikemen and arquebusiers, light cavalry equipped with short lances and “adarga” leather shields, and "cavalaria acobertada" barded heavy cavalry, the Duque having his own halberdier guards.

One year later, the Portuguese were driving into mainland Morocco. A battle ensued (the Battle of the Alcaides), where, according to sources, the Portuguese infantry adopted a formation equivalent to a “Tercio”, i.e., with pikemen in the centre and arquebusier corners and wings. The adoption of this formation at an early stage could be explained by the fact tthat Portuguese and Spanish cooperated in North Africa, and Portuguese contingents were often sent at Spanish request: for instance, in the naval aspect of that cooperation, at the storming of Tunis in 1535, Prince D. Luis of Portugal led the Portuguese contingent whose biggest ship – requested by Charles V himself - was the S. Joao Baptista “Botafogo”, a huge galleon armed with some 366 artillery pieces.

As this cooperation had been happening for ages, one shouldn’t find it strange that a “Tercio” formation has been adopted in 1514. This organisation was probably also used in mainland Portugal, but the only data we have after 1514 is from 1578 and 1580 (battle of Alcântara, Lisbon). Giving the adoption, even at an earlier stage, of contemporary infantry formations, one may be led to believe that the metropolitan army, like most Western Europe, followed Spanish military lines.

However, if the adoption of modern tactics is to be postulated, in terms of military and social organization, Portugal remained a backward Nation. Since the Ordenanças where resisted by every social strata, the military system remained the privately raised companies, usually sent abroad - Brazil, India or Morocco - were fighting was a constant.

According to the Regimento da Guerra, by Martin Afonso de Melo, the Portuguese forces, at least in North Africa, tended to have a greater proportion of arquebusiers than pikemen: “(…) in each squadron they have two companies of arquebusiers, not counting on the arquebusiers present in each [standard] company (…) since we don't fight others than un-armoured men, we need only a small force of pikes, and we need more arquebuses, so that we can damage the enemy from a distance, and that's why I give each company of 300 men, 170 arquebusiers, and 130 pikemen, because when we make a squadron out of them, it can be surrounded with 3 lines [of arquebusiers], which is the best way, and it allows us to have free arquebusiers, since this is the thing that's more useful in Africa, and the one we use more often”.

Regarding the Empire, while some sieges took place during this period, most of the actions fought in Morocco, however, were cavalry skirmishes. The Portuguese fought in Moorish fashion, using short lances and “adarga” shields and the tactics of hit and run of old.

In the Orient, most of the actions fought by the Portuguese were either naval encounters or siege operations. Nonetheless some land battles and small actions also took place, such as, the defence of Cochim in 1504 and the battles against the Somalis in Abyssinia, who shaped the Horn of Africa as we know it today.

In 1639 Somali tribes under Ahmad ibn Ibrihim al-Ghazi, a.k.a. “Gran” (left-handed), invaded the country and defeated the Abyssinian army of Emperor Lebna Dengel Dawut. His successor, Emperor Gelawdewos, asked the Portuguese for help. As soon as he heard the news the Governor of India , D. Estevão da Gama realized the importance of the situation and sent his own brother, D. Cristovão da Gama, with a small expedition of "400 soldiers, very well armed and spirited, and with them [they had] more than 600 “espingardas” [arquebuses]." In a passage in Castanhoso's book the Portuguese are reported to have used lances against the Somali cavalry. The Portuguese Royal Flag was of carmine and white embroidered cloth with a red Cross of Christ while the captains had pennons of blue and white cloth with the same cross. In the presence of the dowager Queen, the Portuguese performed a military tattoo, changing formation several times, evolving into “caracole” formations and ending the show with an arquebus volley.

With the Abyssinian morale in their lowest and the Emperor's army scattered or simply in flight, it was the Portuguese who actually bore the brunt of the fighting. They were extremely successful but then, in late August 1542, a battle took place (Battle of Wofla) in which they were severely beaten by much larger Somali and Ottoman forces, including artillerists and janissaries. D. Cristovão was imprisoned, tortured and then behead.

Eventually, however, the Abyssinians recovered their spirit, their numbers grew and with the remaining Portuguese they managed to defeat the Somalis at Wayna Daga (near Lake Tana). The “Gran” was shot dead by the Portuguese who also slaughtered the remaining Ottoman janissaries. Therefore, the Portuguese are acknowledge to have saved Abyssinia from becoming a Muslim nation.

At the Dutch siege of Macau in 1622, African slaves were employed by the defending party with great success, as their ferocity made the Dutch loose their spirit. After the Portuguese surrender in Qishm their Arab auxiliaries were handed over to the Persian who promptly executed them.

In 1603 some thirty Portuguese soldiers and merchantmen led by Salvador Ribeiro de Sousa, later joined by 800 Portuguese volunteers and 1000 Burmese allies, defeated several larger Burmese armies in Pegu.

In Brazil the Portuguese fought both the Indians and, in 1624 and in 1630-45, the Dutch who were at war with the Habsburgs (at a time the Portuguese royal house). As the weak Portuguese forces were unable to stand up against the powerful WIC in open battle, they trusted instead in the "little war", devised by Matias de Albuquerque and managed by both the local Portuguese colonists and by the “Terços de homens pardos” (mulattos), “homens negros” (black men) and “índios” (Indians). This proved effective as the Dutch were not prepared to fight this guerrilla warfare "tropical style". In 1645, five years after the Restoration of the independence in Lisbon, the Portuguese colonists under Dutch domination revolted and soon after the Dutch were surrounded in their cities. The Portuguese crown also secretly dispatched some reinforcements despite diplomatic constrains. The WIC tried to quell the rebellion but in two separate battles at the Guararapes range, in 1648 and 1649, the Dutch were soundly defeated by much smaller but more mobile and better led Portuguese forces. As a consequence, Brazil was finally liberated in 1654.

The bulk of the Portuguese forces in Timor was actually made of Timorese warriors led by the mestiços Topazes or "Black Portuguese". An insignificant Portuguese garrison (a company) occupied the city of Lifau.

Likewise, as in Timor the small Portuguese forces in Africa were supplemented by native auxiliaries or allies such as the Catholic Congolese or the cannibal Jagas/Imbangala.

In Ceylon the Portuguese fought several pitched battles against some native independent kingdoms, especially against Kandy and Uva in the central part of the island. Each Portuguese "arraial" was made of some Portuguese companies and up to twenty times as much "lascarins" auxiliaries armed either with long spears or pikes or with bows and arquebuses. When fighting against the Sinhalese elephants the Portuguese used fire spears to frighten the beasts.

Regarding tactics, like I said earlier, many of the land actions were skirmishes with Moorish troops involving small light cavalry units where personal charisma and courage often determined the outcome of the fight.

In terms of weaponry, the Portuguese quickly adopter firearms ("espingardas" and "arcabuzes"), first of German and Bohemian origin, then Portuguese made. After 1511, Indian expertise was gradually employed to the extent that some of the highly appreciated craftsmen from Goa were sent to Lisbon to lend their mastery to that city’s Arsenal. By 1540 the crossbow had been completely abandoned, although it still figured in the Ordenanças of D. Sebastião (1570). The Portuguese also used spears and 4.80m long (at least) pikes, often reduced to half-pikes.

The Portuguese used light, breech-loading fast shooting artillery along with some heavier types. In Ethiopia the expeditionary Portuguese forces not only used 8 breech-loading guns but also used about 10 or 11 makeshift multi-barrel guns made of arquebuses tied together in a cart.

Main references:

Barata, Manuel Themudo; Teixeira, Nuno Severiano (ed.). Nova História Militar de Portugal, Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores, 2004, vol. 2

Barros, João de. Da Ásia, Décadas, Lisboa: Regia Oficina Tipográfica, 1778. Biblioteca Nacional, scanned on-line edition

Boxer, Charles Ralph. O Império Marítimo Português 1415 - 1825; Lisboa: Edições 70, 1992

Castanhoso, Miguel de (not. Neves Águas). História das cousas que o mui esforçado capitão D. Cristóvão da Gama fez nos Reinos do Preste João com quatrocentos portugueses que consigo levou, Mem Martins: Publicações Europa-América, 1988

Costa, João Paulo Oliveira e; Rodrigues, Vítor Luís Gaspar. A Batalha dos Alcaides 1514. No apogeu da presença portuguesa em Marrocos; Lisboa: Tribuna da História, 2007

Couto, Diogo. Da Ásia, Décadas, Lisboa: Regia Oficina Tipográfica, 1778. Biblioteca Nacional, scanned on-line edition

Coutinho, Lopo de Sousa. O primeiro cerco de Diu; Lisboa: Alfa - Biblioteca da Expansão Portuguesa nº 41, 1989

Daehnhardt, Rainer. Homens, Espadas e Tomates. Porto: Edições Nova Acrópole, 1996

Daehnhardt, Rainer. Espingarda feiticeira. A introdução da arma de fogo pelos Portugueses no Extremo Oriente/ The Bewitched gun. The introduction of the firearm in the Far East by the Portuguese . Lisboa: Texto Editora, 1994

Lemos, Jorge de. História dos cercos de Malaca, Lisboa: Biblioteca Nacional, 1982

Melo, Martim Afonso de. Regimento da Guerra in Provas da Historia Genealogica da Caza Real Portuguesa, 1744.

Monteiro, Saturnino. Batalhas e Combates da Marinha Portuguesa, Vol. II. Livraria Sá da Costa, 1ª Edição, 1991.

Mousinho, Manuel de Abreu (not. Maria Paula Caetano). Breve discurso em que se conta a conquista do Reino do Pegú na Índia Oriental, Mem Martins: Publicações Europa-América, 1990

Ribeiro, João. Fatalidade História da Ilha de Ceilão; Lisboa: Alfa - Biblioteca da Expansão Portuguesa nº 3, 1989

Although the king controlled most aspects of the military apparatus, the nobility still performed many of its old duties, namely the raising of military contingents made either of paid (professional) soldiers or vassals, this including the household (servants, etc.). Personal connections were very important and it was common for a commander to prefer the services of kin or friends as lesser commanders. Experience, however, was not discarded so “old” soldiers were often promoted or sought after for advice.

Throughout the whole XVI century every king, from D. Manuel I to D. Sebastião, tried to implement a system of Ordenanças in which every men were supposed to have certain pieces of equipment (javelins, spears, pikes, swords, crossbows of arquebuses, depending on the person’s income) and every “Concelho” (county) was supposed to raise companies lead by local men. So, in a way, while still adopting a Medieval sense of duty towards the king (the military service, as an obligation, was not paid), these Ordenanças would create a very Modern militia or citizen army, not a standing army but a reserve from which the king could easily raise one.

These Ordenanças, however, had at least two flaws:

Firstly, in the economic sense, this system overburdened the citizens as it was up to them, and not the State, to support the cost of their equipment. Moreover, military service was seldom paid, even to professional soldiers. And the status of these Ordenanças implied that men had to attend periodic musters (in the original Ordenanças, or Regimento dos Capitães-Mores of 1570, these musters would take place every week!), an obligation that was opposed by every man.

Secondly, contrary to established aristocratic prerogatives, the captains of these companies (250 men strong divided in 10 “esquadras”) were chosen from among the notable men in the villages, which meant that the old privileges of the nobility, stipulating that nobles should lead, would be phased out (many nobles lived outside their properties, in Lisbon, for instance). Likewise, people of different “conditions”, that is, of different social strata, opposed to be enrolled into the same company, lesser nobility, or “escudeiros” (squires) preferring to serve in the cavalry instead, even if they couldn’t supply a horse!

Therefore, it is only from 1570 onwards that D. Sebastião, unlike his grandfather D. João III, managed to implement a system of Ordenanças, adapted to the social situation of his time, and managed to raise 4 infantry “Terços” of 2000 men each.

So, for the most part of this period, the army was privately raised, each captain or noble being issued a letter allowing him to raise a company or even an host. The army remained a professional organism where personal links were more important than the obligation towards the State.

The best part of the Portuguese forces was made of “nobres” (nobles), “fidalgos” (lesser nobility) and “soldados” (professional soldiers), most of them expert swordsmen. Their swordsmanship was only equalled by their rashness: although few could stand against Portuguese in solo fights, organised enemies, such as the Dutch, could face and defeat them, in spite of their own losses. This deficiency was due to poor command (often given to inexperienced nobles due only to their social status), carelessness and sometimes an acute lack of training. It is also noteworthy that by mid-XVII cent. many of the soldiers were convicts and vagabonds sent from Lisbon's prisons.

The “casados” (married men) were a social group within the colonists (“moradores”) who were often married with native women. Together with the “mercadores” (merchantmen) they fought in times of need.

While the Portuguese dominion over their colonies was achieved through clear strategic thinking, technological innovations, decisive naval battles and the conquest or foundation of strategic cities such as Goa, Ormuz, Malacca, S. Salvador da Baía, Recife or Rio de Janeiro, the maintenance of the Empire was achieved through political gambling, conversions, matrimonial alliances and, most of all, “mestiçagem” (half-bread), a Portuguese specialty. This, however, didn’t happen in Morocco, deemed as a “land of war”, proper for the gentry and nobility who wished to become famous through deeds of arms.

In 1513, in penance for the killing of his first wife, Duque D. Jaime was sent by the king D. Manuel I to storm the rebellious city of Azamor. He paid from his own pockets a 15.000 strong army (13.000 foot, 2000 horses) and Azamor was taken in 2 days. The frescoes at the Ducal Palace of Vila Viçosa show pikemen and arquebusiers, light cavalry equipped with short lances and “adarga” leather shields, and "cavalaria acobertada" barded heavy cavalry, the Duque having his own halberdier guards.

One year later, the Portuguese were driving into mainland Morocco. A battle ensued (the Battle of the Alcaides), where, according to sources, the Portuguese infantry adopted a formation equivalent to a “Tercio”, i.e., with pikemen in the centre and arquebusier corners and wings. The adoption of this formation at an early stage could be explained by the fact tthat Portuguese and Spanish cooperated in North Africa, and Portuguese contingents were often sent at Spanish request: for instance, in the naval aspect of that cooperation, at the storming of Tunis in 1535, Prince D. Luis of Portugal led the Portuguese contingent whose biggest ship – requested by Charles V himself - was the S. Joao Baptista “Botafogo”, a huge galleon armed with some 366 artillery pieces.

As this cooperation had been happening for ages, one shouldn’t find it strange that a “Tercio” formation has been adopted in 1514. This organisation was probably also used in mainland Portugal, but the only data we have after 1514 is from 1578 and 1580 (battle of Alcântara, Lisbon). Giving the adoption, even at an earlier stage, of contemporary infantry formations, one may be led to believe that the metropolitan army, like most Western Europe, followed Spanish military lines.

However, if the adoption of modern tactics is to be postulated, in terms of military and social organization, Portugal remained a backward Nation. Since the Ordenanças where resisted by every social strata, the military system remained the privately raised companies, usually sent abroad - Brazil, India or Morocco - were fighting was a constant.

According to the Regimento da Guerra, by Martin Afonso de Melo, the Portuguese forces, at least in North Africa, tended to have a greater proportion of arquebusiers than pikemen: “(…) in each squadron they have two companies of arquebusiers, not counting on the arquebusiers present in each [standard] company (…) since we don't fight others than un-armoured men, we need only a small force of pikes, and we need more arquebuses, so that we can damage the enemy from a distance, and that's why I give each company of 300 men, 170 arquebusiers, and 130 pikemen, because when we make a squadron out of them, it can be surrounded with 3 lines [of arquebusiers], which is the best way, and it allows us to have free arquebusiers, since this is the thing that's more useful in Africa, and the one we use more often”.

Regarding the Empire, while some sieges took place during this period, most of the actions fought in Morocco, however, were cavalry skirmishes. The Portuguese fought in Moorish fashion, using short lances and “adarga” shields and the tactics of hit and run of old.

In the Orient, most of the actions fought by the Portuguese were either naval encounters or siege operations. Nonetheless some land battles and small actions also took place, such as, the defence of Cochim in 1504 and the battles against the Somalis in Abyssinia, who shaped the Horn of Africa as we know it today.

In 1639 Somali tribes under Ahmad ibn Ibrihim al-Ghazi, a.k.a. “Gran” (left-handed), invaded the country and defeated the Abyssinian army of Emperor Lebna Dengel Dawut. His successor, Emperor Gelawdewos, asked the Portuguese for help. As soon as he heard the news the Governor of India , D. Estevão da Gama realized the importance of the situation and sent his own brother, D. Cristovão da Gama, with a small expedition of "400 soldiers, very well armed and spirited, and with them [they had] more than 600 “espingardas” [arquebuses]." In a passage in Castanhoso's book the Portuguese are reported to have used lances against the Somali cavalry. The Portuguese Royal Flag was of carmine and white embroidered cloth with a red Cross of Christ while the captains had pennons of blue and white cloth with the same cross. In the presence of the dowager Queen, the Portuguese performed a military tattoo, changing formation several times, evolving into “caracole” formations and ending the show with an arquebus volley.

With the Abyssinian morale in their lowest and the Emperor's army scattered or simply in flight, it was the Portuguese who actually bore the brunt of the fighting. They were extremely successful but then, in late August 1542, a battle took place (Battle of Wofla) in which they were severely beaten by much larger Somali and Ottoman forces, including artillerists and janissaries. D. Cristovão was imprisoned, tortured and then behead.

Eventually, however, the Abyssinians recovered their spirit, their numbers grew and with the remaining Portuguese they managed to defeat the Somalis at Wayna Daga (near Lake Tana). The “Gran” was shot dead by the Portuguese who also slaughtered the remaining Ottoman janissaries. Therefore, the Portuguese are acknowledge to have saved Abyssinia from becoming a Muslim nation.

At the Dutch siege of Macau in 1622, African slaves were employed by the defending party with great success, as their ferocity made the Dutch loose their spirit. After the Portuguese surrender in Qishm their Arab auxiliaries were handed over to the Persian who promptly executed them.

In 1603 some thirty Portuguese soldiers and merchantmen led by Salvador Ribeiro de Sousa, later joined by 800 Portuguese volunteers and 1000 Burmese allies, defeated several larger Burmese armies in Pegu.

In Brazil the Portuguese fought both the Indians and, in 1624 and in 1630-45, the Dutch who were at war with the Habsburgs (at a time the Portuguese royal house). As the weak Portuguese forces were unable to stand up against the powerful WIC in open battle, they trusted instead in the "little war", devised by Matias de Albuquerque and managed by both the local Portuguese colonists and by the “Terços de homens pardos” (mulattos), “homens negros” (black men) and “índios” (Indians). This proved effective as the Dutch were not prepared to fight this guerrilla warfare "tropical style". In 1645, five years after the Restoration of the independence in Lisbon, the Portuguese colonists under Dutch domination revolted and soon after the Dutch were surrounded in their cities. The Portuguese crown also secretly dispatched some reinforcements despite diplomatic constrains. The WIC tried to quell the rebellion but in two separate battles at the Guararapes range, in 1648 and 1649, the Dutch were soundly defeated by much smaller but more mobile and better led Portuguese forces. As a consequence, Brazil was finally liberated in 1654.

The bulk of the Portuguese forces in Timor was actually made of Timorese warriors led by the mestiços Topazes or "Black Portuguese". An insignificant Portuguese garrison (a company) occupied the city of Lifau.

Likewise, as in Timor the small Portuguese forces in Africa were supplemented by native auxiliaries or allies such as the Catholic Congolese or the cannibal Jagas/Imbangala.

In Ceylon the Portuguese fought several pitched battles against some native independent kingdoms, especially against Kandy and Uva in the central part of the island. Each Portuguese "arraial" was made of some Portuguese companies and up to twenty times as much "lascarins" auxiliaries armed either with long spears or pikes or with bows and arquebuses. When fighting against the Sinhalese elephants the Portuguese used fire spears to frighten the beasts.

Regarding tactics, like I said earlier, many of the land actions were skirmishes with Moorish troops involving small light cavalry units where personal charisma and courage often determined the outcome of the fight.

In terms of weaponry, the Portuguese quickly adopter firearms ("espingardas" and "arcabuzes"), first of German and Bohemian origin, then Portuguese made. After 1511, Indian expertise was gradually employed to the extent that some of the highly appreciated craftsmen from Goa were sent to Lisbon to lend their mastery to that city’s Arsenal. By 1540 the crossbow had been completely abandoned, although it still figured in the Ordenanças of D. Sebastião (1570). The Portuguese also used spears and 4.80m long (at least) pikes, often reduced to half-pikes.

The Portuguese used light, breech-loading fast shooting artillery along with some heavier types. In Ethiopia the expeditionary Portuguese forces not only used 8 breech-loading guns but also used about 10 or 11 makeshift multi-barrel guns made of arquebuses tied together in a cart.

Main references:

Barata, Manuel Themudo; Teixeira, Nuno Severiano (ed.). Nova História Militar de Portugal, Lisboa: Círculo de Leitores, 2004, vol. 2

Barros, João de. Da Ásia, Décadas, Lisboa: Regia Oficina Tipográfica, 1778. Biblioteca Nacional, scanned on-line edition

Boxer, Charles Ralph. O Império Marítimo Português 1415 - 1825; Lisboa: Edições 70, 1992

Castanhoso, Miguel de (not. Neves Águas). História das cousas que o mui esforçado capitão D. Cristóvão da Gama fez nos Reinos do Preste João com quatrocentos portugueses que consigo levou, Mem Martins: Publicações Europa-América, 1988

Costa, João Paulo Oliveira e; Rodrigues, Vítor Luís Gaspar. A Batalha dos Alcaides 1514. No apogeu da presença portuguesa em Marrocos; Lisboa: Tribuna da História, 2007

Couto, Diogo. Da Ásia, Décadas, Lisboa: Regia Oficina Tipográfica, 1778. Biblioteca Nacional, scanned on-line edition

Coutinho, Lopo de Sousa. O primeiro cerco de Diu; Lisboa: Alfa - Biblioteca da Expansão Portuguesa nº 41, 1989

Daehnhardt, Rainer. Homens, Espadas e Tomates. Porto: Edições Nova Acrópole, 1996

Daehnhardt, Rainer. Espingarda feiticeira. A introdução da arma de fogo pelos Portugueses no Extremo Oriente/ The Bewitched gun. The introduction of the firearm in the Far East by the Portuguese . Lisboa: Texto Editora, 1994

Lemos, Jorge de. História dos cercos de Malaca, Lisboa: Biblioteca Nacional, 1982

Melo, Martim Afonso de. Regimento da Guerra in Provas da Historia Genealogica da Caza Real Portuguesa, 1744.

Monteiro, Saturnino. Batalhas e Combates da Marinha Portuguesa, Vol. II. Livraria Sá da Costa, 1ª Edição, 1991.

Mousinho, Manuel de Abreu (not. Maria Paula Caetano). Breve discurso em que se conta a conquista do Reino do Pegú na Índia Oriental, Mem Martins: Publicações Europa-América, 1990

Ribeiro, João. Fatalidade História da Ilha de Ceilão; Lisboa: Alfa - Biblioteca da Expansão Portuguesa nº 3, 1989

-

pippohispano

- Administrative Corporal - SdKfz 251/1

- Posts: 142

- Joined: Thu Sep 23, 2010 4:39 pm

In the Ordenação sobre os cavalos e armas (Rules for horses and guns) of D. João III (1549), people of “condition” should have: high saddle, corselet with gorge, thigh and arm protections, sword and 20 palm lance; they could also have cuirass and gineta saddle instead; they could also provide, if they didn’t have the corselet they should have arm protections or an adarga shield instead, plus full head protection.

In 1513 Duque D. Jaime had "cavaleiros acobertados" (barded cavalry). Likewise, in 1578 D. Sebastião had a similar unit of a hundred men.

Regarding the use of guns by the cavalry, unlike its Moorish foes, it seems that the Portuguese cavalry seldom used arquebuses or crossbows. Neither the Ordenação sobre os cavalos e armas (Rules for horses and guns) of D. João III (1549) nor the Lei das Armas (Law of the guns) of D. Sebastião (1569) stipulated the use of guns by the cavalry, although that practice was widespread even in the Spanish army (the herreruelos and the harquebusiers made up to 1/5 of the Spanish cavalry in the 1570’s and 1580’s). In 1639, right before the Restauration, all the cavalry in the Kingdom of Algarve (the southern province in mainland Portugal) was equipped with light lance and “adarga” since it was Algarve’s cavalry who, in emergency situations, would support the North African garrisons where that sort of equipment was used.

So, in terms of official regulations, there was no crossbow or arquebus armed cavalry in the 16th century.

However, in 1511, the garrisson of Safim had mounted crossbowmen and there are also some hints regarding gun-armed cavalry in Black Africa:

An ivory statuette of African origin depicts a Portuguese rider using an early type of arquebus. The most interesting aspect of the sculpture lies in a small detail: the man’s pointing finger, instead of being placed where the regular trigger should be, is placed on the stock, right under the fire mechanism. That gives us the precious information that the gun he’s using, and that the African carver saw and accurately reproduced, is an arquebus with the schnapp lunte type of lock, of Bohemian origin, that was used only for a brief period in History, being phased out in the 1530’s or 1540’s (in the Battle of Pavia’s tapestries, the German arquebusiers are using this type of arquebuses). This implies that the statuette was probably made in the first half of the century.

Was this Portuguese "mounted arquebusier" just an eye-catching isolated case or was this a regular sight? Was he a cavalry soldier or a mounted infantry soldier? That is a question that maybe one day will be answered.

In 1513 Duque D. Jaime had "cavaleiros acobertados" (barded cavalry). Likewise, in 1578 D. Sebastião had a similar unit of a hundred men.

Regarding the use of guns by the cavalry, unlike its Moorish foes, it seems that the Portuguese cavalry seldom used arquebuses or crossbows. Neither the Ordenação sobre os cavalos e armas (Rules for horses and guns) of D. João III (1549) nor the Lei das Armas (Law of the guns) of D. Sebastião (1569) stipulated the use of guns by the cavalry, although that practice was widespread even in the Spanish army (the herreruelos and the harquebusiers made up to 1/5 of the Spanish cavalry in the 1570’s and 1580’s). In 1639, right before the Restauration, all the cavalry in the Kingdom of Algarve (the southern province in mainland Portugal) was equipped with light lance and “adarga” since it was Algarve’s cavalry who, in emergency situations, would support the North African garrisons where that sort of equipment was used.

So, in terms of official regulations, there was no crossbow or arquebus armed cavalry in the 16th century.

However, in 1511, the garrisson of Safim had mounted crossbowmen and there are also some hints regarding gun-armed cavalry in Black Africa:

An ivory statuette of African origin depicts a Portuguese rider using an early type of arquebus. The most interesting aspect of the sculpture lies in a small detail: the man’s pointing finger, instead of being placed where the regular trigger should be, is placed on the stock, right under the fire mechanism. That gives us the precious information that the gun he’s using, and that the African carver saw and accurately reproduced, is an arquebus with the schnapp lunte type of lock, of Bohemian origin, that was used only for a brief period in History, being phased out in the 1530’s or 1540’s (in the Battle of Pavia’s tapestries, the German arquebusiers are using this type of arquebuses). This implies that the statuette was probably made in the first half of the century.

Was this Portuguese "mounted arquebusier" just an eye-catching isolated case or was this a regular sight? Was he a cavalry soldier or a mounted infantry soldier? That is a question that maybe one day will be answered.

-

pippohispano

- Administrative Corporal - SdKfz 251/1

- Posts: 142

- Joined: Thu Sep 23, 2010 4:39 pm

In 1511, the garrison of Safim was made of 5 officers; 11 of the captain’s own foot soldiers; 24 of the captain’s squires; 39 of the King’s servants with 95 of their own men; 103 cavalrymen with 54 servants; 111 foot soldiers; 31 mounted crossbowmen with 15 servants; 34 crossbowmen; 32 espingardeiros, 12 bombardiers; 15 atalaias (scouts) and cornets.

So, in this particular case, the ginetes would be roughly 20% ot the total force, and the mounted crossbowmen some 5%.

Cosme, João. A Guarnição de Safim em 1511. Lisboa: Centro de História da Universidade de Lisboa, 2004

In 1514, at the “Battle of the Alcaides”, the Portuguese army was made of 1000 lanças and 1300 or more foot, plus some 2000 Moorish ginetes. Usually a lança would be composed of 1 cavalryman and up to 5 more men, but in this case, as most if not all of the cavalry was made of ginetes, a lança would probably include just one or two other men.

The infantry forces included two well trained and “modern style” 500 men ordenanças companies (a leftover from Duque D. Jaime’s host) plus crossbowmen and espingardeiros (probably evenly divided like at Safim), bombardiers and camp followers.

So, at this battle, if one considers that a lança had between 2 and 3 men, the Portuguese cavalry would made between 25% and 30% of the army.

Costa, João Paulo Oliveira e; Rodrigues, Vítor Luís Gaspar. A Batalha dos Alcaides 1514. No apogeu da presença portuguesa em Marrocos; Lisboa: Tribuna da História, 2007

So, in this particular case, the ginetes would be roughly 20% ot the total force, and the mounted crossbowmen some 5%.

Cosme, João. A Guarnição de Safim em 1511. Lisboa: Centro de História da Universidade de Lisboa, 2004

In 1514, at the “Battle of the Alcaides”, the Portuguese army was made of 1000 lanças and 1300 or more foot, plus some 2000 Moorish ginetes. Usually a lança would be composed of 1 cavalryman and up to 5 more men, but in this case, as most if not all of the cavalry was made of ginetes, a lança would probably include just one or two other men.

The infantry forces included two well trained and “modern style” 500 men ordenanças companies (a leftover from Duque D. Jaime’s host) plus crossbowmen and espingardeiros (probably evenly divided like at Safim), bombardiers and camp followers.

So, at this battle, if one considers that a lança had between 2 and 3 men, the Portuguese cavalry would made between 25% and 30% of the army.

Costa, João Paulo Oliveira e; Rodrigues, Vítor Luís Gaspar. A Batalha dos Alcaides 1514. No apogeu da presença portuguesa em Marrocos; Lisboa: Tribuna da História, 2007

-

pippohispano

- Administrative Corporal - SdKfz 251/1

- Posts: 142

- Joined: Thu Sep 23, 2010 4:39 pm

In the famous battle of Alcácer Quibir, where the Portuguese army was soundly defeated, there were three foreign contingents, one of German and Walloon origin, under Martin of Burgundy; another one from Spain, under Alonso de Aguilar, and a third one from Italy under Thomas Stukley.

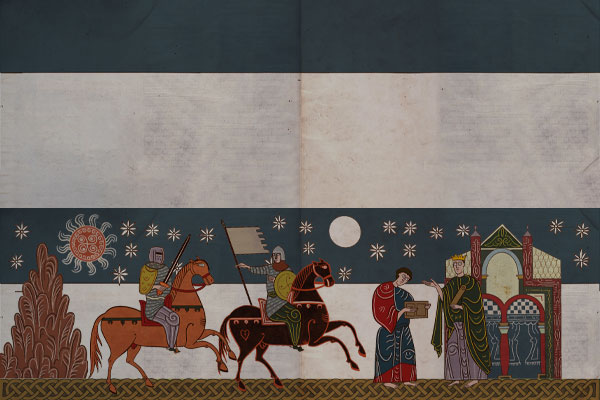

In this picture, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... _kopie.jpg, in a book written by Miguel Leitão de Andrade in 1629 (the author was a survivor from the battle), one can see the pike & shot formations, the light (whith adarga shield) and heavy cavalry and the independent arquebusier companies.

Of special interest, the flags: most of them depict either the Cross of Christ or the Cross of Burgundy, also used by the Portuguese. But there are two that, in my opinion, represent two of the foreign bodies: a knotted Cross of Burgundy, for the Spanish, and a flag with a lion for the Germans and Walloons (probably the lion of Flanders or maybe Brabant).

In this picture, http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/c ... _kopie.jpg, in a book written by Miguel Leitão de Andrade in 1629 (the author was a survivor from the battle), one can see the pike & shot formations, the light (whith adarga shield) and heavy cavalry and the independent arquebusier companies.

Of special interest, the flags: most of them depict either the Cross of Christ or the Cross of Burgundy, also used by the Portuguese. But there are two that, in my opinion, represent two of the foreign bodies: a knotted Cross of Burgundy, for the Spanish, and a flag with a lion for the Germans and Walloons (probably the lion of Flanders or maybe Brabant).

-

pippohispano

- Administrative Corporal - SdKfz 251/1

- Posts: 142

- Joined: Thu Sep 23, 2010 4:39 pm

Hi Montesa.

Unfortunately no, I don't have much information regarding Spanish units in Catalonia.

However, if you follow this link http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Felipe_da_Silva, I've put a reference to the book "Campaña de Cataluña de 1644" which I think you may find online.

You should also search this excellent site http://www.tercios.org/index.html, in Spanish. If you cannot find what you're searching for, ask the webmaster.

For another subject (the Portuguese-Spanish war or War of the Restauration), you have this site http://www.tercios.org/index.html. The author may have some info on that subject or at least give you the contacts of people who know.

Unfortunately no, I don't have much information regarding Spanish units in Catalonia.

However, if you follow this link http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Felipe_da_Silva, I've put a reference to the book "Campaña de Cataluña de 1644" which I think you may find online.

You should also search this excellent site http://www.tercios.org/index.html, in Spanish. If you cannot find what you're searching for, ask the webmaster.

For another subject (the Portuguese-Spanish war or War of the Restauration), you have this site http://www.tercios.org/index.html. The author may have some info on that subject or at least give you the contacts of people who know.

Thanks for your help, they aren't unknown to me. I have also Historia de los movimientos, separación y guerra de Cataluña of Francisco Manuel de Melo that was a portuguese commander. Not to be confused with Francisco de Melo, the spanish commander in Rocroi that was also portuguese.

There are more webs as http://ejercitodeflandes.blogspot.com or http://usuarios.multimania.es/ao1617/tercios.html

There are more webs as http://ejercitodeflandes.blogspot.com or http://usuarios.multimania.es/ao1617/tercios.html

-

pippohispano

- Administrative Corporal - SdKfz 251/1

- Posts: 142

- Joined: Thu Sep 23, 2010 4:39 pm

-

pippohispano

- Administrative Corporal - SdKfz 251/1

- Posts: 142

- Joined: Thu Sep 23, 2010 4:39 pm

Unfortunately, as always.

Now, reverting to D. Sebastião's army at Alcácer Quibir, in a couple of days or so I'll post here some more informations regarding the cavalry.

Besides the Cavaleiros acobertados (equivalent to Gendarmes), there were hundreds more of noble cavalry. I believe that most were equiped as prescribed in the Law of the Horses and Weapons of 1549, i.e, they would be armoured, would ride unarmoured horses and had spears. I'll check it and post it here.

Now, reverting to D. Sebastião's army at Alcácer Quibir, in a couple of days or so I'll post here some more informations regarding the cavalry.

Besides the Cavaleiros acobertados (equivalent to Gendarmes), there were hundreds more of noble cavalry. I believe that most were equiped as prescribed in the Law of the Horses and Weapons of 1549, i.e, they would be armoured, would ride unarmoured horses and had spears. I'll check it and post it here.

-

pippohispano

- Administrative Corporal - SdKfz 251/1

- Posts: 142

- Joined: Thu Sep 23, 2010 4:39 pm

Now, lets go to Alcácer Quibir. I'll base my writtings on Luís Costa e Sousa's book.

The Portuguese infantry was composed by four Ordenças Terços (Tercios) and Terço dos Aventureiros, all similar to any contemporary Spanish Tercio.

Of the Ordenças, two came from Lisbon and Estremadura (the territory north of Lisbon) and the other two from Alentejo and Algarve. These Terços were made of draftees, that is, men used to be summoned to regular exercices, just like the modern days' Swiss militia army. The best Terços were the ones from Alentejo and Algarve, made from people deemed to be warlike and used to war: the people from Algarve was used to fight the Moors and was quick to dispatch help to the north African garrisons when needed.

The Terço dos Aventureiros was made of veterans from North Africa and elsewhere, and nobles who couln't afford a horse. They were the best infantry in the field.

The cavalry:

Between 200 and 600 horses (ginetes) from Tangiers;

In one of the anounymous reports from the battle refered to by Costa e Sousa, besides ginetes, there were light cavalry "like stradiots" on the Portuguese side. These could be mounted arquebusiers, as the ginetes didn't have guns. In 1613 the garisson of Mazagão had 60 mounted arquebusiers, as well as 60 ginetes;

900 heavily armoured horses in squadrons of 25 men each. Luís de Oxeda refers that these horses were “barded with armour in the old Portuguese style”. They could be also equiped as prescribed in the Law of the Horses of 1549, i.e., armoured knight with lance riding an unarmoured horse. But as Luís de Oxeda was an eye witness I’ll just have to stick to it.

The OOB (page 63):

First Line (from left to right)– 600 acobertados and the King; 2100 Spanish under Alonso de Aguilar; 600 Italians under Thomas Stukley; 1400 Portuguese under Cristóvão de Távora; 600 arquebusiers from Tanger led by Alexandre Moreira; 2700 Flemish and Germans led by Martin of Burgundy; 300 acobertados led by the Duque of Aveiro; the Moorish ally contingent under Mulei Mahamet (250 horses and 400 arquebusiers).

The centre – the Terços of Lisbon and Estremadura, led by Bezerra Castelhano and Vasco da Silveira with two wings of shooters. (5000 men in all)

Third line - the Terços of Alentejo (Francisco de Távora) and Algarve (Miguel de Noronha) with a line of musketeers (some 4000 men).

The Portuguese infantry was composed by four Ordenças Terços (Tercios) and Terço dos Aventureiros, all similar to any contemporary Spanish Tercio.

Of the Ordenças, two came from Lisbon and Estremadura (the territory north of Lisbon) and the other two from Alentejo and Algarve. These Terços were made of draftees, that is, men used to be summoned to regular exercices, just like the modern days' Swiss militia army. The best Terços were the ones from Alentejo and Algarve, made from people deemed to be warlike and used to war: the people from Algarve was used to fight the Moors and was quick to dispatch help to the north African garrisons when needed.

The Terço dos Aventureiros was made of veterans from North Africa and elsewhere, and nobles who couln't afford a horse. They were the best infantry in the field.

The cavalry:

Between 200 and 600 horses (ginetes) from Tangiers;

In one of the anounymous reports from the battle refered to by Costa e Sousa, besides ginetes, there were light cavalry "like stradiots" on the Portuguese side. These could be mounted arquebusiers, as the ginetes didn't have guns. In 1613 the garisson of Mazagão had 60 mounted arquebusiers, as well as 60 ginetes;

900 heavily armoured horses in squadrons of 25 men each. Luís de Oxeda refers that these horses were “barded with armour in the old Portuguese style”. They could be also equiped as prescribed in the Law of the Horses of 1549, i.e., armoured knight with lance riding an unarmoured horse. But as Luís de Oxeda was an eye witness I’ll just have to stick to it.

The OOB (page 63):

First Line (from left to right)– 600 acobertados and the King; 2100 Spanish under Alonso de Aguilar; 600 Italians under Thomas Stukley; 1400 Portuguese under Cristóvão de Távora; 600 arquebusiers from Tanger led by Alexandre Moreira; 2700 Flemish and Germans led by Martin of Burgundy; 300 acobertados led by the Duque of Aveiro; the Moorish ally contingent under Mulei Mahamet (250 horses and 400 arquebusiers).

The centre – the Terços of Lisbon and Estremadura, led by Bezerra Castelhano and Vasco da Silveira with two wings of shooters. (5000 men in all)

Third line - the Terços of Alentejo (Francisco de Távora) and Algarve (Miguel de Noronha) with a line of musketeers (some 4000 men).